Week 5: Ship's Computer

Creating a diegetic computer console was a pain, but also really fun.

This week I made Running Late even more like a spacecraft by adding a functioning console to the mix. This terminal will be the gateway to several systems having to do with the overall ship, as opposed to the ones with exposed components you fiddle with. It turned out that making a computer show up in the game is so much harder than I'd thought it would be.

The Terminal Problem

I imagine most sci-fi games have this challenge. You want terminals that are functional but also that look good and integrate with the environment. Especially if this is a first-person perspective game—the whole point is the immersion. Just having a UI pop up on top of the scene would work but doesn't really hit the note that I want to hit. Running Late is about vibes, and I need the art to match.

I wanted a terminal you could walk up to, see clearly from multiple angles, and interact with like actual hardware. And this meant the little details too—the screen should have the interior cabin lights reflect off the glass of the CRT, it should have a faint green phosphor tint underneath the colored pixels, it should physically curve with the curved surface of the screen.

Easier Said than Done

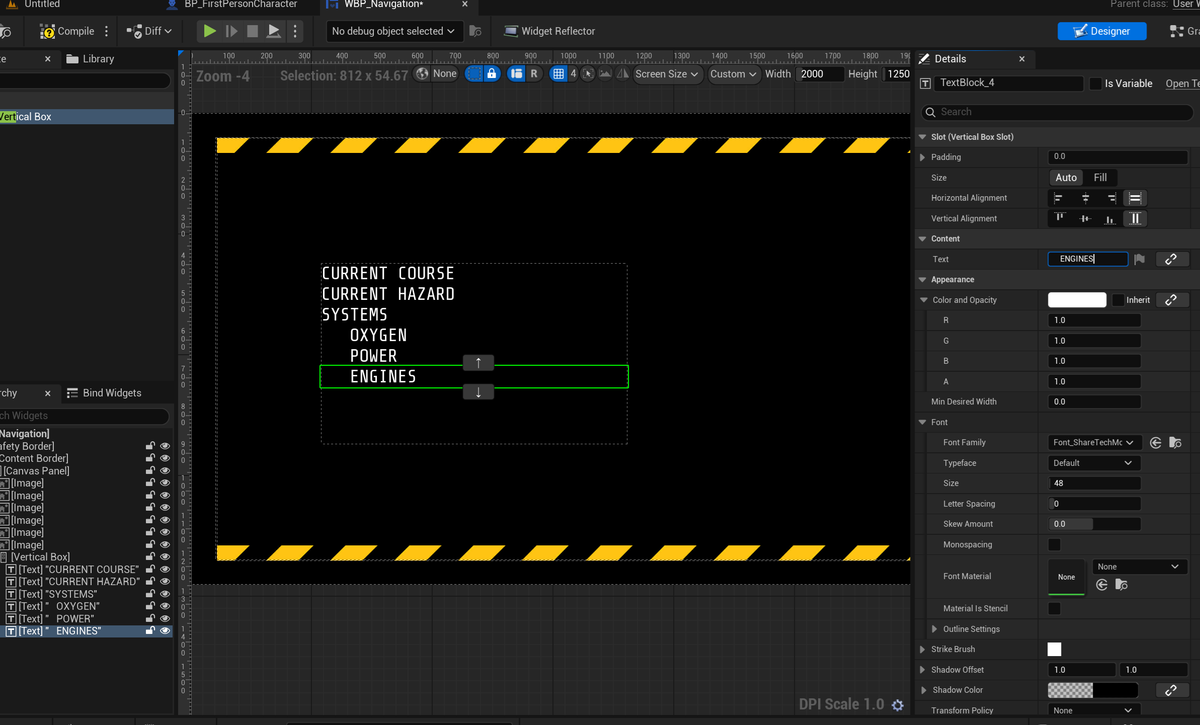

Unreal has a mechanism for showing a UI in 3D space, but that mechanism only really handles planes well, and (as far as I could tell) it doesn't let you layer additional materials on the widget. If I wanted to have an electrical storm fritz up the display or even if I wanted to just tint the controls, I was going to need a better solution.

I found a way to take a UI Widget and render it to part of a static mesh. This let me draw the UI onto the surface of the screen with any material I wanted. I got both the glass effects and the curved screen. Just one problem. I needed a way to click on the screen like an object you're interacting with. That used a bit of deep Unreal magic. If you're interested in the details, you'll see them in this week's field notes.

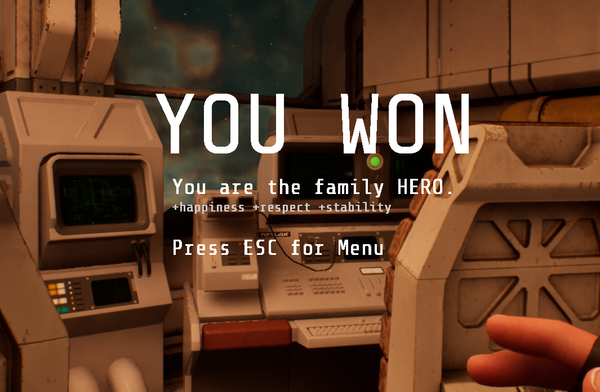

Short of it is, the result feels really authentic—you're interacting with a real computer screen in the world.

Orienting the Ship

Once I had interactive screen displays, I could make them control the ship. There's now a screen for correcting the course by moving a targeting crosshair over a dot that represents the correct course angle. While you're on that screen, you can use the movement controls to angle the ship's pitch, yaw, or roll. Of course, there's a bit of inertia - fire the thrusters too long and you'll overshoot the target.

System Integration

All this plugs into the power system, same as oxygen. When the power goes out, the terminal goes dark and you can't make course corrections. The ship keeps drifting according to whatever momentum it had. And the check systems light monitors your ship's attitude and alerts you when you're too far off course. But it's really the environmental integration that sells the illusion. As the ship rotates, the star field outside the cockpit windows rotates as well.

The Experience

The real test was watching it all work together. Lights go out, terminal goes dark, ship starts drifting. You grab the flashlight, navigate to the electrical panel, diagnose the blown fuse, swap in a replacement. Power comes back, lights restore, terminal boots up. You see the crosshair has drifted way off center while you were working in the dark. Now you're applying counter-thrust and monitoring oxygen levels, hoping nothing else breaks and that you haven't lost too much time.

Roaring Engines

Next week I'm building the engine control system. Thrust management, efficiency curves, engine wear—systems that will make course corrections feel consequential. I need to see if I can find some really good engine thruster sounds to mix into the audio. I want the visceral feel as the thrusters kick on to be sweet.