Field Notes: Making In-World Screens

Making a terminal is trickier than it looks.

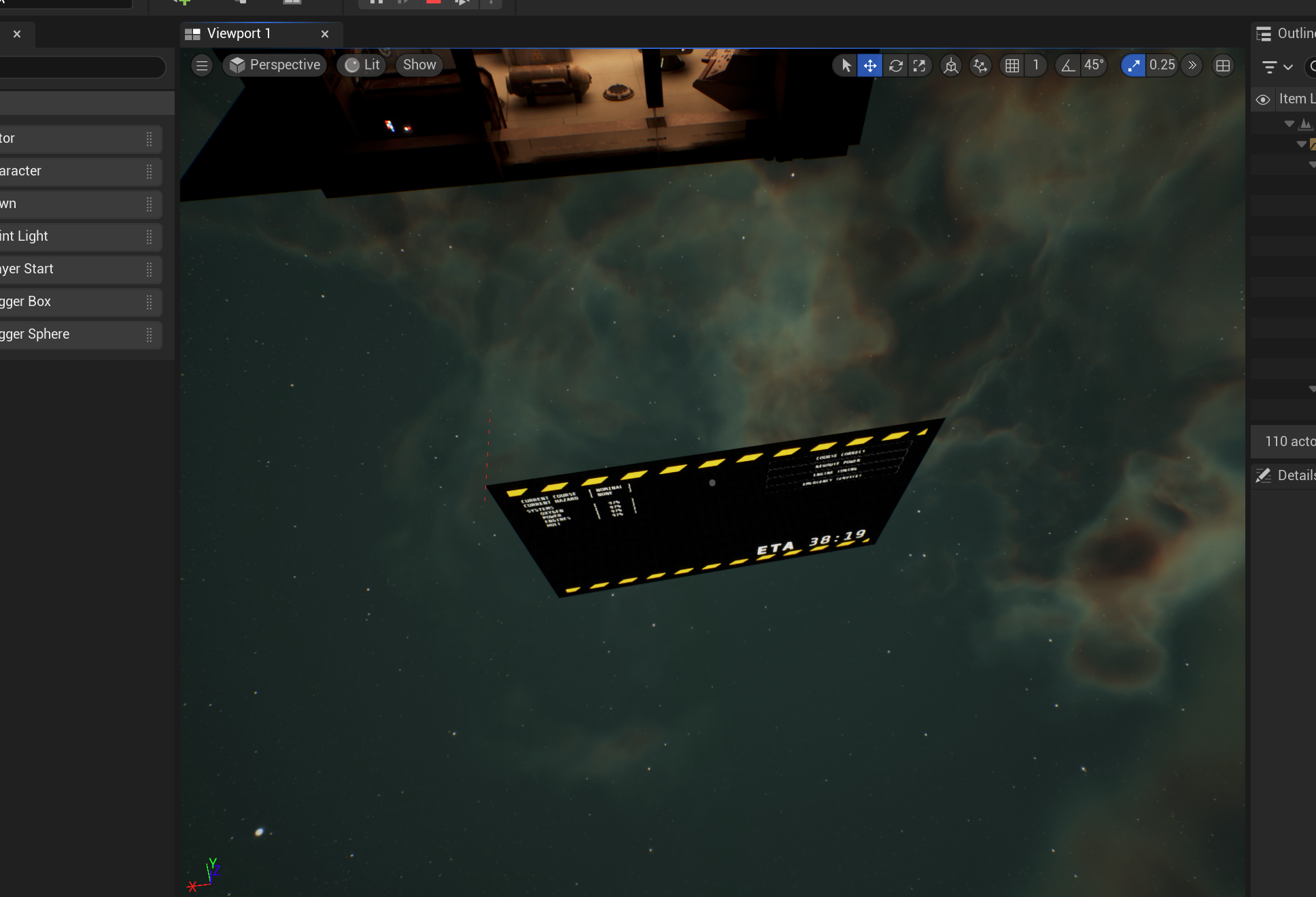

The navigation terminal looked great as a static prop, but as soon as I tried to make it interactive, I hit a wall that became the most technical challenge of the project so far.

Engine Frustration

I needed three things that Unreal Engine doesn't want to give you all together.

- Interactive UI. The buttons on the screen should respond to clicks. I can get this from a standard widget component.

- Material effects. I wanted glassy reflections, phosphor glow, and eventually interference from magnetic storms. I could get this from a material.

- 3D geometry. The screen I was projecting the UI onto was the curved surface of a CRT monitor. You can curve a widget component, but it loses its interactivity.

So widget components give you interactivity but no effects and materials give you enhanced visuals with no interaction. What's a dev to do?

The Hack

I spent hours banging my head on a virtual monitor before I found the answer: I can build a bridge between both systems and get everything.

I had an off-screen widget component render the UI. Every tick, I grab the rendered texture of that component and use that as a texture input to a material. That material adds additional properties like smoothness for glass reflection. Finally, I use that material on the part of the nav console's model that displays the screen, giving me the UI rendered with additional material effects.

That's the first half, with material effects and 3D geometry, but now I needed to add back in the interactivity.

So also on tick, I raycast from the mouse cursor forward in the world. If the raycast hits the screen, I ask Unreal what part of the texture we hit with a less documented feature of Unreal called Find Collision UV. (Finding this took a while. I had to enable this via project settings just to be able to use the feature at all.)

Once I have those coordinates, I can manipulate a widget interaction component (also off-screen), that looks at the widget component. Based on where the texture was hit, I adjust the position of that interaction component to point at the same place on the widget. This provides all the same interactivity a mouse cursor would provide.

The result is a terminal that feels completely authentic. The screen has proper glass reflections from the interior lighting, and includes a green phosphor tint over the white graphics, just like a real CRT monitor. When you click on the screen, you're genuinely interacting with the curved 3D surface, so there's no pixel displacement.

More importantly, I think I can use this for any additional screens I might want in the game. With thirteen potential screens, there's all sorts of fun I can have with these interfaces integrating perfectly with the environment.

Lessons Learned

The cosmic void technique from Week 2 (invisible-but-outlineable objects) taught me that Unreal CAN do things that are deeply surprising. I never expected a raycast to tell me what texture position I landed on for the model I hit. But it turns out that this was exactly the answer I needed. Sometimes the best solutions come from combining systems in ways the documentation never explicitly mentions.

Next Steps

With diegetic UI solved, I can focus on what the terminals actually do rather than how they get displayed. I'm already prototyping engine tuning, with actual turnable wheels for adjusting fuel mixes. This is the kind of technique that will carry over into future games, too. As cliche as it feels to say, I feel like every day at the editor I'm leveling up, and I'm excited about where I can take all this.