Field Notes: Interfaces And Decoupling

Preventing spaghetti from day one.

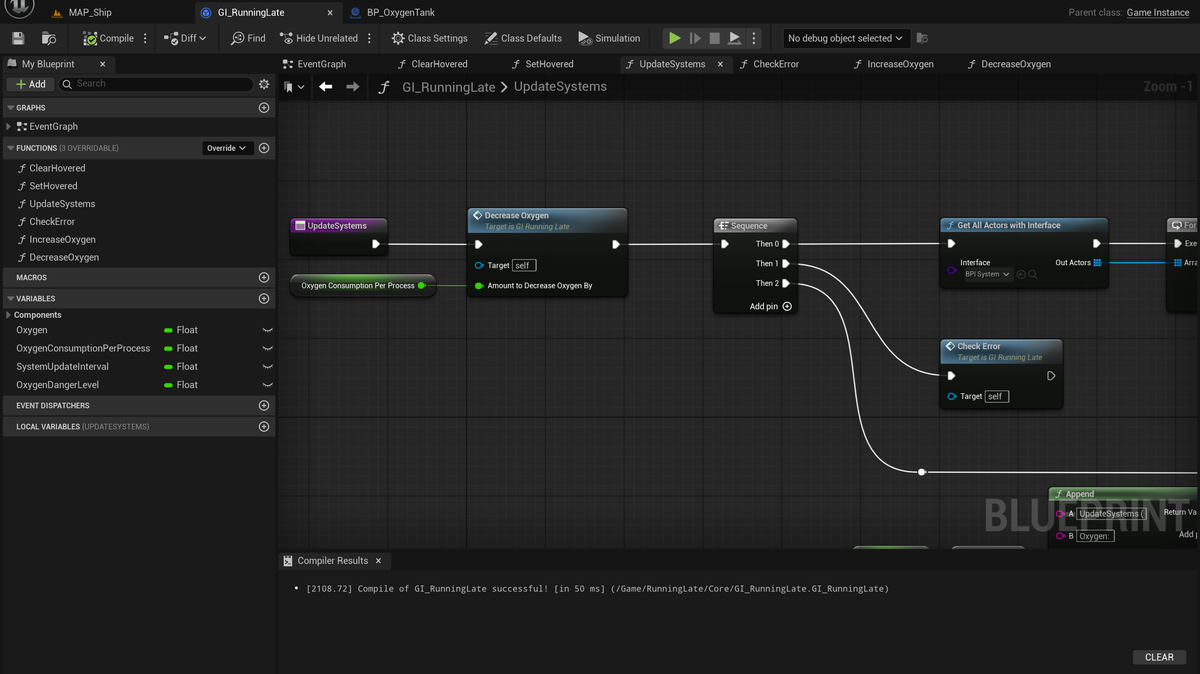

So I was building the oxygen system this week, but I kept thinking about what comes next. Power systems, navigation, engines. All these ship systems need to coordinate without turning into a complete mess of dependencies.

I ran into the problem immediately: how do I build this in an extensible way, that scales beyond just the current system?

The Spaghetti Problem

My first instinct was to go simple: have systems talk to each other directly. The Game Instance (which manages oxygen) talks to the oxygen tank directly. The Oxygen tank talks to the filters. Update every thirty seconds or so, and done!

But I could see where this was heading. Even handling just the one system was a mass of casts and hard references. What happens when I have six different systems all trying to reference each other? What if I want to add a new system later? Suddenly I'm editing code in five different places just to wire up one new component.

The Interface Solution

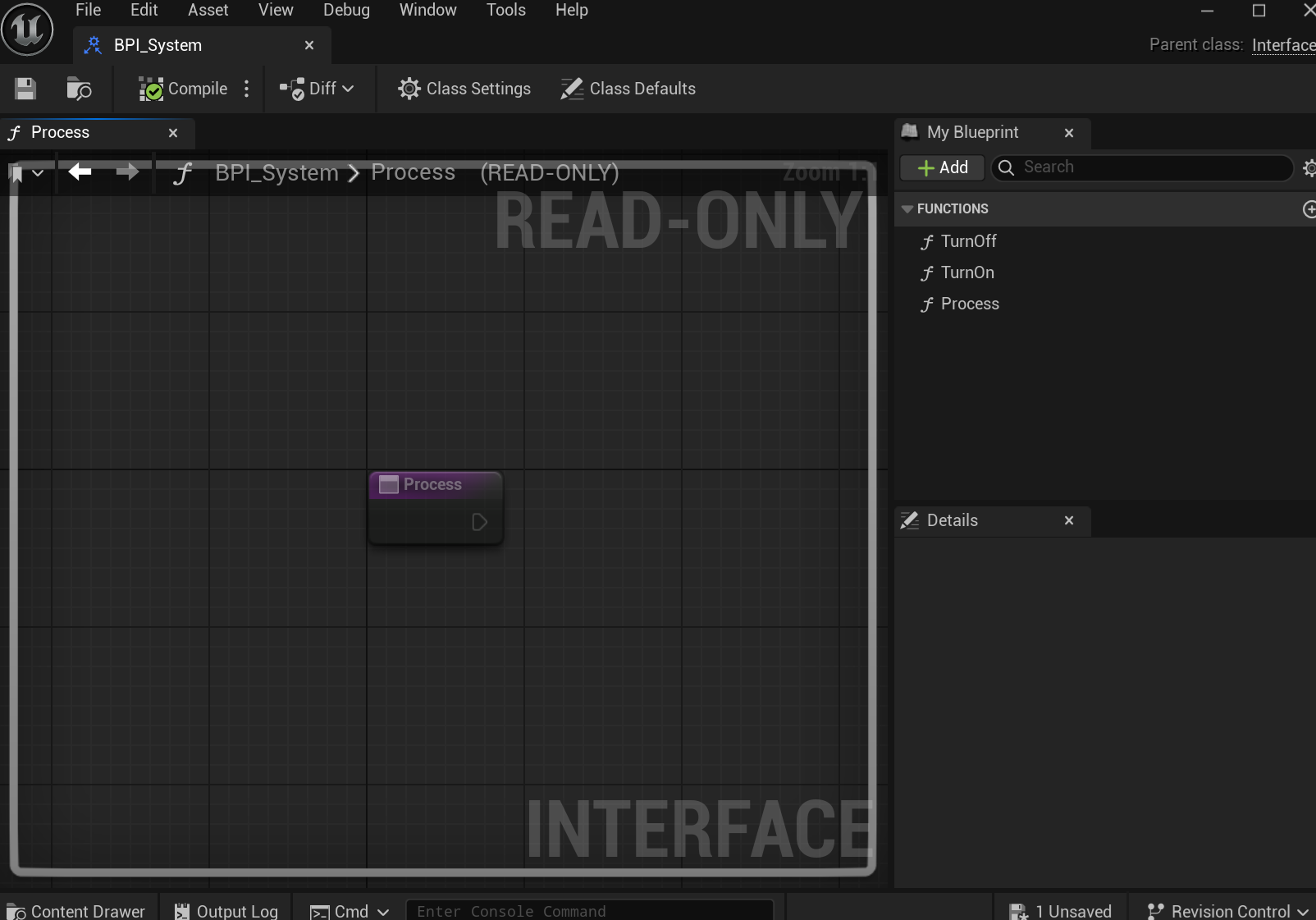

Instead, I created an interface. It's basically a contract that says "any ship system must have a Process() function." That's it. No complex requirements, no specific implementation details. Just, "when asked to update yourself, do what you gotta do."

The oxygen tanks each implement this interface. When their Process() function gets called, they check their filters, generate oxygen, degrade components, whatever. The Game Instance doesn't care about the details.

Automatic Discovery

Here's the elegance of using an interface. In the Game Instance timer, it doesn't look for specific systems or maintain a hand-coded list of actors. Instead, it uses "Get All Actors with Interface" to find everything in the level that implements that interface. Then it just calls Process() on each one.

The master controller has no idea what systems are actually running. It doesn't know about oxygen or power or navigation. It just finds everything that can update itself and asks it to do so. And if I decide to add a new system that I hadn't imagined when I first started the project—a situation I am certain will happen eventually—I won't need to touch Game Instance in order to invoke that new system's code.

The power system I'm building next week? It'll implement the same interface and immediately start getting called every thirty seconds alongside the oxygen system. The master controller will discover it automatically.

Loose Coupling, Tight Cohesion

This is one of those programming patterns that sounds academic but actually makes development so much smoother. Systems are loosely coupled. They don't know about each other directly. But they're part of a cohesive whole through the shared interface.

It means I can focus on building each system individually without worrying about how it integrates with everything else. The integration happens automatically through the interface.

And when systems do need to share information, they can do it through the Game Instance—a central place for ship-wide state like cabin oxygen levels or power status. Clean and centralized.